Waterfall Jumper Sam Patch: 1820s American Daredevil

In the 1820s, a mill worker named Sam Patch captured the imagination of much of the American public with a series of death-defying leaps from waterfalls and other high, dangerous spots. Sam’s daredevil exploits drew large crowds and lots of media attention, aided by his skill at self-promotion.

In our celebrity-saturated culture, one might think the public’s fascination with show business and celebrities is a relatively recent phenomenon. Certainly, the advent of movies, radio, and television in the 20th century increased the public’s awareness of and interest in celebrities, and the rapid growth of cable TV and the Internet has fueled an explosion in the demand for celebrity news. But showmen and celebrities captivated America far earlier, as Sam Patch’s story illustrates.

Pawtucket Falls, Rhode Island: Sam Develops His Jumping Skills

Sam Patch was born into modest circumstances in Reading, Massachusetts, in 1799. When Sam was seven years old, the family moved to Pawtucket, Rhode Island, the premier textile milling town in the United States. Sam, like many other children, got a job in the mills. He became a mule spinner at Samuel Slater’s mill. (A spinning mule is a machine used to spin cotton fiber into yarn.)

Like many other boys and young men in Pawtucket, Sam amused himself by jumping off walls, roofs, and other high places. Sam developed considerable jumping skills as he entertained fellow workers by jumping at the Pawtucket Falls of the Blackstone River.

Great Falls, Paterson, New Jersey: The Jersey Jumper

Around 1820, Sam moved to Paterson, New Jersey, to work in Paterson’s growing textile industry. He became a boss mule spinner at the Hamilton Mills, in the industrial district near the Great Falls of the Passaic River (also commonly known as the Passaic Falls or the Paterson Falls).

In 1827, an entrepreneur named Timothy Crane began building a bridge across the falls. Crane had purchased land on the far side of the falls that had been picnic grounds for mill workers and their families. He converted the land to manicured gardens and built a bar and restaurant to cater to the wealthier residents of the area. Crane also built a wooden bridge to cross the falls.

William Guy Walls, Falls of the Passaic (between 1815 and 1825). (Brooklyn Museum Dick S. Ramsay Fund, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The opening of the bridge on September 30 was a big event: the factories were closed and a large crowd gathered. But Sam Patch stole the show from Crane and his celebration, wowing the crowd by jumping from the cliff at the falls some 77 feet (23 meters) into the swirling waters below.

Accounts differ as to the circumstances of Sam’s jump. According to some reports, he had planned the leap as a workingman’s protest against Crane and the conversion of the picnic areas to a private playground for the rich. Others said that Sam was drunk and decided to jump at the spur of the moment to retrieve a roller that had fallen from the apparatus being used to move the bridge into place. Some even said that a jilted Sam had jumped for love.

Sam himself denied that he was drunk or lovelorn. He maintained that jumping was an art requiring knowledge and courage, which he had perfected through practice. In any event, Sam, the “Jersey Jumper,” was energized by the crowd’s enthusiastic reaction to his feat. He jumped at the falls again on the 4th of July 1828, on a day when Crane was mounting Paterson’s first commercial fireworks display. A third jump came on July 19, before a crowd larger than Paterson’s population.

Beyond Paterson: The Yankee Leaper on Tour

Sam’s jumping fame began to spread beyond Paterson. On August 6, 1828, Sam leaped from the high mast of a sloop in the Hudson River at Hoboken, New Jersey, in a jump that was publicized in advance in the New York newspapers. In announcing the “eccentric novelty” of Sam’s Hoboken jump to its readers, the New-York Enquirer hailed Sam’s “wonderful and intrepid leaps from the Peake of Paterson Falls, to the abyss below.”

Sam’s successful Hoboken jump was widely reported in the press, and Sam became a celebrity. He took his act on the road, traveling on his “Jumping Tour” with a pet fox and later with a pet bear. As he moved beyond New Jersey, he jumped from bridges, cliffs, and other dangerous high places at various spots along the East Coast. He now styled himself “The Yankee Leaper,” boasting “There’s no mistake in Sam Patch!”

Niagara Falls: Sam's Unprecedented "Aero-Nautical Feat"

As his fame increased, Sam was offered $75 (equal to about $2,500 in 2023) by a group of hotel owners to jump at Niagara Falls in October 1829. No one had ever survived a jump at Niagara.

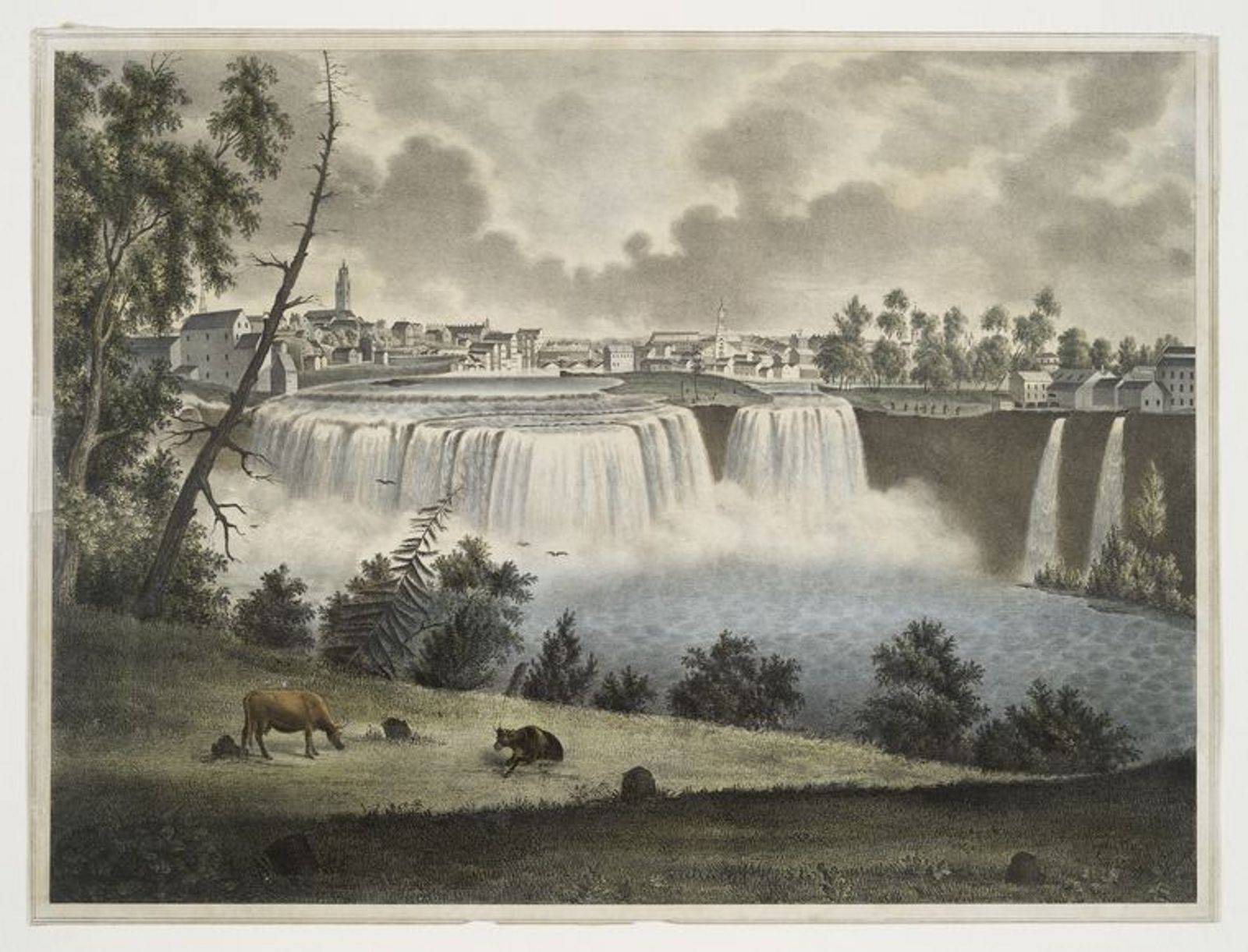

Alvan Fisher, A General View of the Falls of Niagara (1820). (Smithsonian American Art Museum, CC0/Public domain)

Sam’s jump was scheduled for October 6, but he arrived too late to make the jump, so it was rescheduled for the next day. On October 7, he made a successful jump of about 85 feet (26 meters). As the New York Evening Post described it on October 21 (reprinting an October 15 dispatch from the Upper Canada Colonial Advocate):

“On Wednesday, the 7th inst. the celebrated Sam Patch actually leaped over the falls of Niagara into the abyss below. A ladder was projected from Goat Island about 40 feet down, on which Sam walked out clad in white, and with great deliberation put his hands close to his side and jumped from the platform into the midst of that vast gulf of foaming waters from which none of human kind had ever before emerged in life. Sam, however, furnished in his own person an extraordinary proof of the power which self-possession joined with determined resolution gives to man. While the boats below were on the look out for him, he had in one minute reached the shore unnoticed and unhurt, and was heard on the beach singing as merrily as if altogether unconscious of having performed an act so extraordinary as almost to appear an incredible fable. Sam Patch has immortalized himself—he has done what mortal never did before—has precipitated himself eighty-five feet in one leap; that leap into the mighty cavern of Niagara’s Cataract; and survives the romantic feat uninjured!”

Sam's Second Niagara Falls Jump

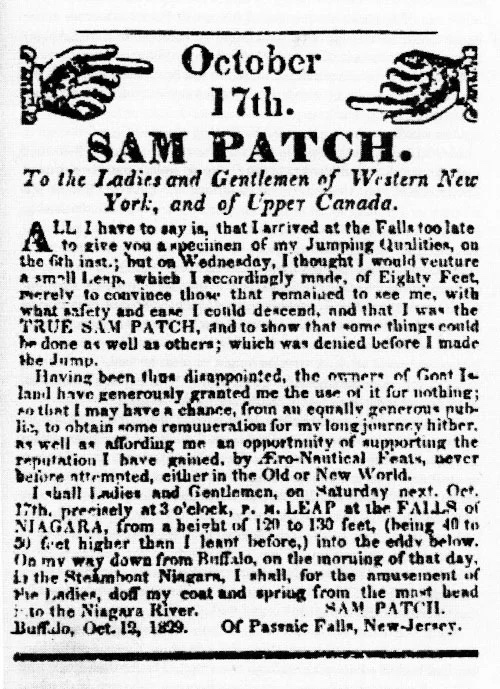

Advertising handbill for Sam Patch’s second jump at Niagara Falls, October 17, 1829.

But the small size of the crowd on October 7 disappointed Sam, so he arranged for a second jump on Saturday, October 17, and distributed promotional handbills to publicize it. As promised in the handbill, he also jumped from the 50-foot (15-meter) masthead of the steamboat Niagara on his way to the falls. This time some 10,000 spectators witnessed his leap at the falls. Sam thrilled the crowd by jumping about 120 feet (37 meters) from a platform built at the top of a ladder that was chained to the cliff wall, into the churning, aerated waters below the falls.

After his Niagara Falls jumps, Sam’s fame grew even more, as word spread of his “Aero-Nautical Feats, never before attempted, either in the Old or New World.”

Genesee Falls, Rochester, New York: Higher Yet!

Before returning to his home in New Jersey, Sam planned one more stop on his Jumping Tour: the Upper Falls of the Genesee River near Rochester, New York. This 97-foot (30-meter) drop was almost as spectacular as Niagara Falls.

Sam’s jump was arranged for Friday, November 6, at 2 p.m. Before a crowd estimated at between 6,000 and 8,000 people, he climbed with his bear to a rock ledge in the middle of the river, 100 feet (30 meters) above the water. After first pushing the bear off the ledge and seeing it swim safely to shore, Sam jumped. The crowd cheered as he surfaced in the water below.

The Upper Falls of the Genesee at Rochester, mid-1800s. (From The New York Public Library)

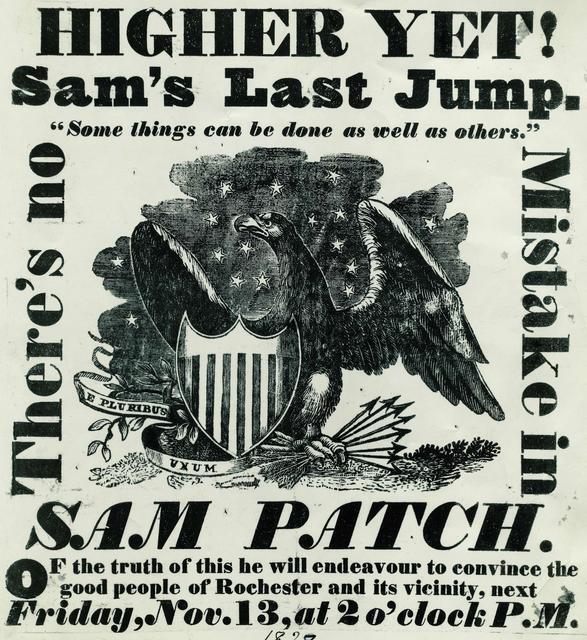

Apparently, however, the jump did not raise as much money from the spectators as Sam had hoped for. He decided to make a second jump a week later, on Friday the 13th. This would be a more daring feat than the first one: instead of jumping from the rock ledge, Sam had a platform built 25 feet above the ledge, raising the height of his jump to 125 feet (38 meters).

Advertisement for Sam Patch’s final jump, November 1829. (Rochester Public Library Local History Division, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The second jump—“Higher Yet!”—was publicized throughout the area with posters proclaiming “Sam’s Last Jump!” This boast was to prove prescient. In front of 8,000 spectators, Sam jumped into the icy water but never surfaced. Observers noted that he did not jump with his usual erect form, and his body slammed into the water.

Many people believed that Sam had survived but had gone into hiding to build his legend, only to make a triumphant reappearance later. But four months later, Sam’s frozen body was found downriver near Lake Ontario. The Anti-Masonic Enquirer newspaper reported on March 23, 1830, that Sam’s body was “perfectly preserved,” and that his black handkerchief was tied around him as it had been when he made his final leap.

Waterfall Jumper Sam Patch: Enduring Folk Hero

Sam was gone, but his legend persisted. Jumping—over fences, over store counters—became a national pastime among young and old, as everyone tried to “do Sam Patch.” His motto, “Some things can be done as well as others,” was a catchphrase around the country.

Some preachers spoke out against the “strange and savage curiosity” of the crowds that had gone to see him, with some even suggesting that the spectators were complicit in his death. But by and large, Sam was a folk hero. President Andrew Jackson, a folk hero in his own right, named his favorite horse Sam Patch.

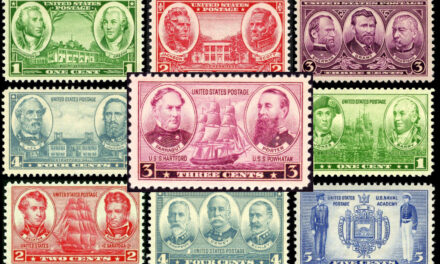

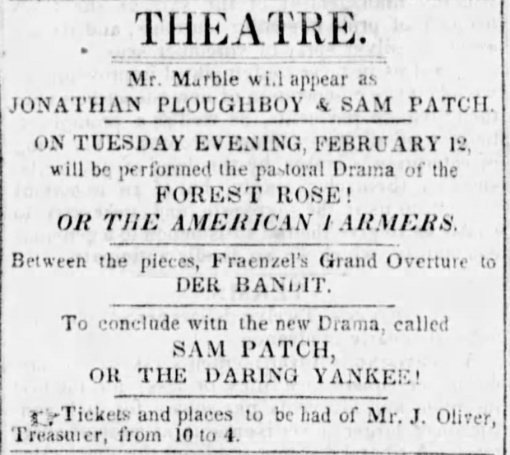

Sam was celebrated in the theater and in literature. A few years after his death, comedian-actor Dan Marble played Sam in a traveling show, “Sam Patch, or the Daring Yankee,” first in western cities and then in Boston and New York. Sam was celebrated in poetry as “The Great Descender, Mighty Patch!”

Theater advertisement for Dan Marble in "Sam Patch, or the Daring Yankee!" (The Mississippi Free Trader, Natchez, Mississippi, February 12, 1839, via Newspapers.com)

Some of America’s most prominent 19th-century novelists mentioned Sam in their stories. In his 1835 sketch “Rochester,” Nathaniel Hawthorne tells how Sam, “the jumper of cataracts,” “took his last leap, and alighted in the other world.” Herman Melville’s young sea-going hero in Redburn (1849) recounts how he eventually conquered his nerves and “felt as fearless … as Sam Patch on the cliff of Niagara.” In William Dean Howells’s novel Their Wedding Journey (1872), newlyweds Basil and Isabel March visit Rochester on their honeymoon. When Isabel admits she’s never heard of Sam Patch, Basil takes her to the falls and tells her the whole story of Sam’s fatal leap:

“Have you really, then, never heard of the man who invented the saying, ‘Some things can be done as well as others,’ and proved it by jumping over Niagara Falls twice? Spurred on by this belief he attempted the leap of the Genesee Falls. The leap was easy enough, but the coming up again was another matter. He failed in that. It was the one thing that could not be done as well as others.”

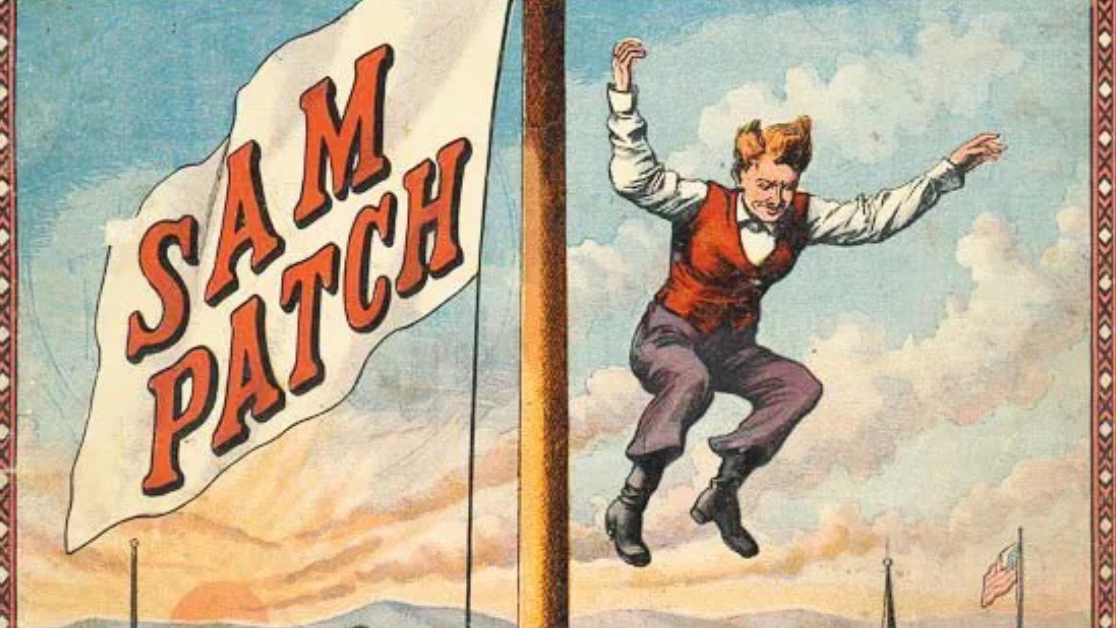

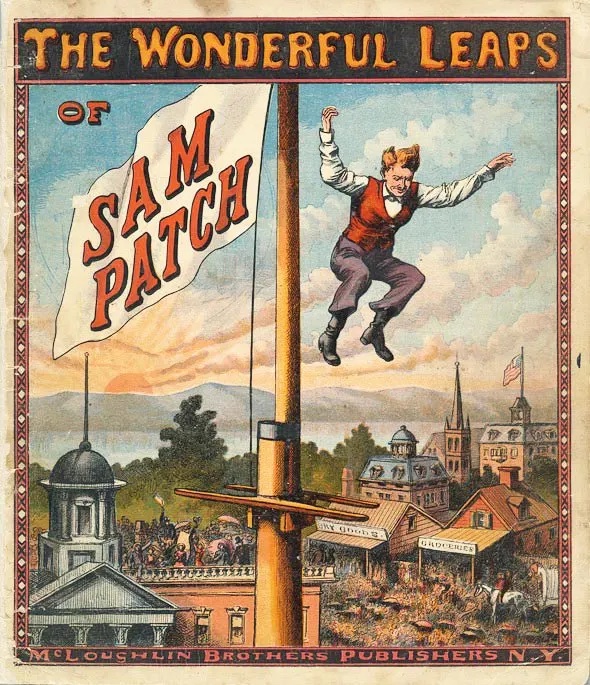

Cover illustration for The Wonderful Leaps of Sam Patch, published by McLaughlin Brothers, 1870. (The Mary Faulk Markiewicz Collection of Children’s Books at the University of Rochester)

In 1870, the McLoughlin Brothers company published a children’s picture book, The Wonderful Leaps of Sam Patch. The book included stories and illustrations of numerous leaps, some factual and some invented. The moral of the story (because all children’s books must have a moral): look before you leap.

For years after his death, people continued to believe Sam was still alive. There were frequent Sam Patch sightings around the country. As one recent commentator put it, “the 19th century Evel Knievel turned into the 19th century Elvis.” (The Memory Palace, Podcast Episode 17 “Plummeting Approval”)

For a few brief years in the late 1820s, daredevil Sam Patch was a star. He gave ordinary Americans, especially working-class people like himself, a chance to dream of big things. Deeds that were larger than life. The adulation of crowds. Fame.

That’s not so different from the allure that celebrities and the entertainment business provide today.

Copyright © Brian Lokker 2013, 2023. An earlier version of this article was published on HubPages.com in 2013 and was subsequently featured on Owlcation.com.