How Coffee Fueled the 1932 Brazilian Olympic Team

Brazil’s 1932 Olympic team would not have gotten to the Xth Olympiad in Los Angeles without coffee. The Brazilian athletes did not have much success in the Olympic competitions. But the story of the 1932 Brazilian Olympic team’s unique journey to the Olympic Games will always have a place in both Olympic lore and coffee history.

Brazil's Coffee Crisis

In 1932, Brazil was the world’s largest coffee producer, accounting for 80 percent of the world’s coffee. Brazil’s coffee industry had expanded rapidly in the 50 years from 1880 to 1930. The São Paulo coffee interests dominated both the economy and the government, along with the dairy industry of Minas Gerais. As a result, these five decades became known as the “café com leite” (coffee with milk) period in Brazilian history.

When the Great Depression ravaged the world’s economy, it hit Brazil’s coffee industry hard. World coffee prices fell and buyers canceled coffee contracts. Overproduction of coffee had been a persistent problem, but now it was a crisis.

The government of President Getúlio Vargas created the National Coffee Council to combat the coffee crisis. The Council purchased part of the São Paulo coffee crop. It disposed of some of this coffee through barter. For example, it used exchange agreements to obtain wheat from the United States in 1931 and coal from Germany in 1932. The Council also destroyed millions of bags of coffee either by burning them or dumping them into the sea.

Surplus coffee is loaded onto a steamer at the dock in Rio de Janeiro in 1931 in order to dump it in the ocean. (Daily News, New York, August 27, 1931, p. 22, via newspapers.com)

Financing the 1932 Brazilian Olympic Team with Coffee

Brazil’s coffee crisis led to an opportunity for its Olympic athletes. Brazil had sent athletes to the Olympic Games twice before. Nineteen Brazilian men competed in Antwerp in 1920, with the Brazilians winning three medals in shooting events. In 1924, Brazil sent 12 men to the Paris Olympics but won no medals. Brazil did not participate in the 1928 Games in Amsterdam.

In January 1932, the national sports federation announced that Brazil would send a team to the summer Olympic Games in Los Angeles. In May, the American Ambassador in Rio de Janeiro confirmed Brazil’s participation in a cablegram to the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. He also shared the news that Brazil would use a unique scheme to finance its team. The 1932 Brazilian Olympic team would be fueled by coffee.

Brazil’s sports federation chartered a merchant steamer, the S.S. Itaquicê, to transport the athletes to Los Angeles. The federation asked the National Coffee Council to help defray expenses by putting together a cargo of coffee. Coffee growers agreed to donate thousands of bags of coffee. The plan was to sell some at ports along the way and sell the rest in California.

Given the Brazilian coffee crisis, this looked like a win-win solution. It would get the Olympic athletes to Los Angeles, and it would get more Brazilian coffee to market.

The Olympic Athletes Join the Coffee Cargo Aboard the Itaquicê

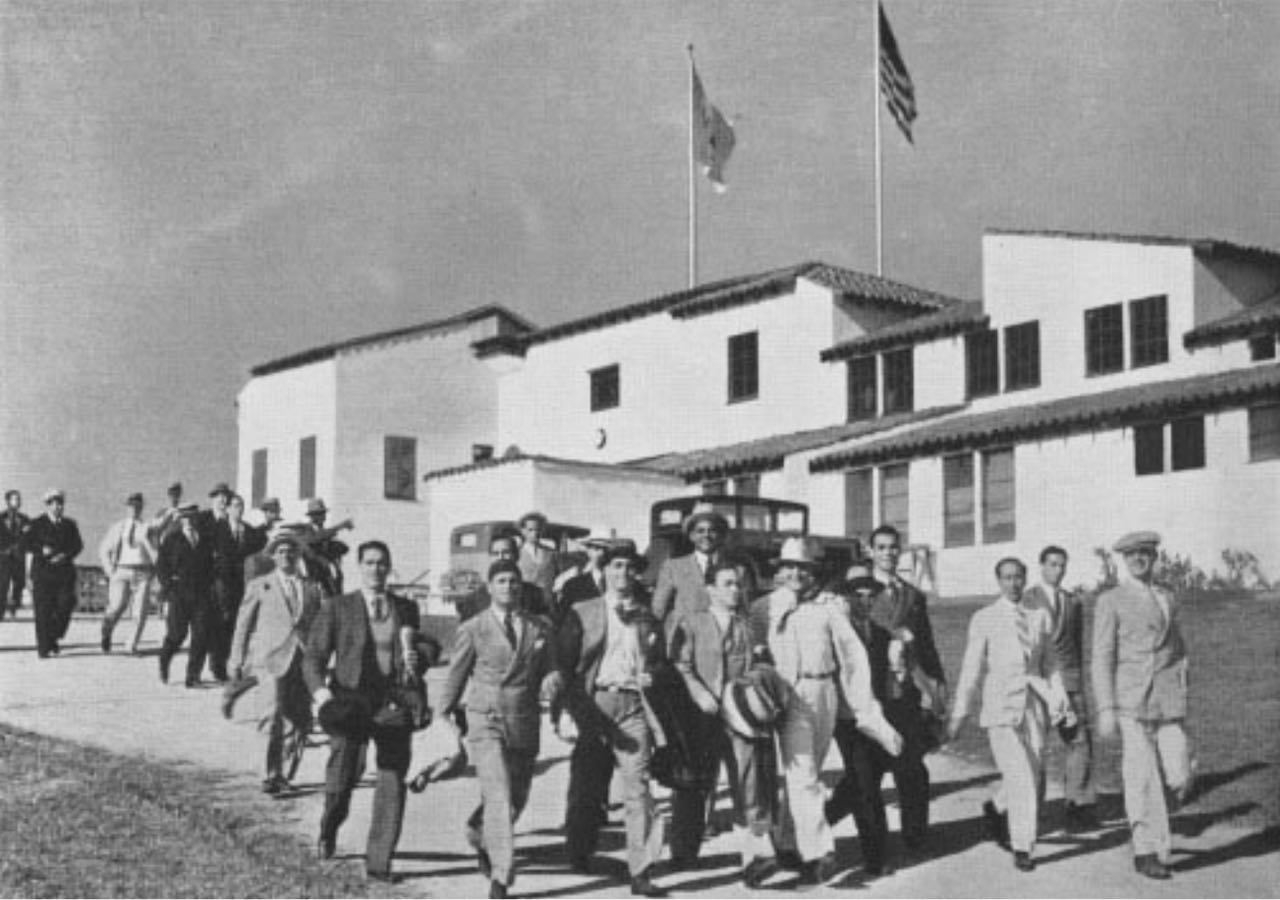

The Itaquicê left Rio De Janeiro on June 25. Contemporary newspaper reports vary as to the number of athletes and others aboard. But according to the Official Report published by the Xth Olympiade Committee in 1933, the Brazilian delegation included 87 athletes, along with 9 officials and staff members and 13 members of the press. The ship also carried a Navy band, friends and family members of the athletes, and other spectators.

Reports of the amount of coffee on board also vary. Most accounts put the cargo at 55,000 bags of coffee, while others say 50,000 bags. Either way, it was a large quantity of coffee, and the athletes were expected to help sell some of it.

The 1932 Brazil Olympic delegation aboard the S.S. Itaquicê en route from Rio de Janeiro to Los Angeles. (S.S. Itaquicê: Navios e Portos: A História da Marinha Mercante Brasileira, crediting ACERJ)

The Itaquicê had a long voyage ahead of her when she left Rio de Janeiro. Sailing to Los Angeles by the most direct route via the Panama Canal, the ship would travel some 7,197 nautical miles (equivalent to 8,282 land miles). This was about 2,000 miles longer than Brazil’s previous Olympic teams had traveled to get to the 1920 and 1924 Games in Europe. Stopping at ports along the way would also lengthen the voyage.

The Brazilians hoped to sell some of the coffee at Port of Spain in Trinidad. The Itaquicê stopped there on July 6. The athletes went ashore to exercise, but they were unable to sell much if any coffee.

When they reached the Panama Canal, money was tight. To avoid the canal transit fees, the Brazilians argued that the Itaquicê was a naval vessel. She did carry two cannons. But their argument was unsuccessful, and they had to pay the fees.

On July 11, the Itaquicê passed through the Panama Canal with most of her coffee cargo still aboard. She was only the second vessel sailing under the Brazilian flag to transit the canal. At the Pacific-side port of Balboa, the Brazilian water polo team beat a Canal Zone scrub team 20–0 in a practice match. (Unfortunately, the water polo team did not fare as well in Los Angeles—see below.) The Itaquicê then headed out for the final leg of her journey to Los Angeles.

Revolution in Brazil Adds to Athletes’ California Money Woes

The Itaquicê arrived at the Port of Los Angeles in San Pedro at 5:45 a.m. on Friday, July 22. After their long voyage, the athletes were looking forward to disembarking and heading to the Olympic Village to prepare for the start of the games on Saturday the 30th. But the lack of funds that had plagued the trip from the start threw a monkey wrench into their plans.

On July 9, while the Brazilian Olympic athletes were at sea, the State of São Paulo had rebelled against President Vargas’s federal government. One consequence of what became known as the Constitutionalist Revolution was a blockade of the main coffee port at Santos. Another consequence was a delay in obtaining additional funds from Brazil for the Olympic delegation’s expenses.

The Brazilians were initially able to scrape together only enough money to enable 24 of their athletes to pay the required $1 per head fee to disembark. More athletes managed to leave the ship and go to the Olympic Village in the next couple of days. But others—at least 20, according to news reports—had to stay on the Itaquicê and forgo their Olympic dreams.

The first Brazilian athletes arrive at the Olympic Village (The Games of the Xth Olympiad Los Angeles 1932 Official Report, p. 263)

Meanwhile, the Itaquicê offloaded some 22,000 bags of coffee at the Port of Los Angeles. It marked the largest coffee cargo ever discharged at the port. But about half of the Brazilian coffee cargo still remained to be sold. So while the athletes from Brazil got ready for the 1932 Olympic Games, the rest of the coffee from Brazil sailed for San Francisco on the Itaquicê on July 25.

Unfortunately, the Brazilians failed to pay $600 in dockage charges in Los Angeles before they left. Customs brokers Swayne & Hoyt Ltd., who had unloaded the coffee, filed a libel (a suit in admiralty) against the Itaquicê in the U.S. District Cout in San Francisco. The ship was detained in San Francisco for more than a week while the legal difficulties were sorted out.

Finally, on August 4, the Itaquicê received permission to return to Los Angeles. But coffee buyers in San Francisco had taken less of the coffee than expected, and some 8,000 bags were still on board.

From Coffee Merchants to Olympic Competitors

Once most of the Brazilian Olympic athletes were ashore, they could leave the coffee woes of the Itaquicê behind and concentrate on the Olympic events ahead. Brazilian athletes were registered for men’s athletics (track and field), men’s and women’s swimming, including men’s water polo, rowing, and shooting.

The competitions kicked off on July 31 with various track and field events. Among the 18 Brazilian men registered for track and field competitions were some top-notch athletes with reasonable hopes for Olympic success.

Stars included Sylvio de Magalhães Padilha, the Brazilian and South American record holder in the 100-meter and 400-meter hurdles. Padilha was competing in the 400-meter hurdles, the first track event of the Olympics, with teammate Carlos America dos Reis Junior. Unfortunately for Brazil, both Padilha and Reis finished last in their respective heats and did not advance. Star sprinter José Xavier de Almeida turned in the best performance in the first day’s events. He finished second in his heat in the first trials of the 100-meter dash. However, he failed to advance past the second trials.

Five of Brazil’s brightest Olympic hopes: (1) José Xavier de Almeida, sprinter; (2) Sylvio de Magalhães Padilha, hurdler; (3) Domingo Puglisi, 400-meter runner; (4) Maria Lenk, swimmer; and (5) unidentified, most likely Lucio Almeida Prado de Castro, pole vaulter. (The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn, New York, July 25, 1932, p. 3, via Newspapers.com)

But the first day of the competition also produced the best contribution to the 1932 Brazilian Olympic story (besides the coffee!), courtesy of runner Adalberto Cardoso. He had been one of the athletes who could not disembark in Los Angeles before the Itaquicê departed for San Francisco.

But Cardoso was determined to compete in the Olympics. He left the ship in San Francisco and hitchhiked to Los Angeles. Traveling all night without sleep, he arrived at Olympic Stadium only four minutes before the 5:30 p.m. start of the 10,000-meter run. He made it to the starting line with seconds to spare. After such an ordeal, it was hardly surprising that he finished last. But other athletes and spectators alike applauded Cardoso’s determination as a true example of the Olympic spirit.

On August 3, Brazil finally got its first—and only—track and field point (points were awarded for first through sixth place). Lucio Almeida Prado de Castro finished sixth in the pole vault with a mark of 12 feet 9-1/2 inches.

On August 12, Brazil added three more Olympic points, thanks to its rowers. The two-man crew with coxswain, composed of José Ramalbo at the stroke position, Estavam João Strata in the bow, and Francisco Carlos Bricio as coxswain, earned the points with a fourth-place finish.

If Adalberto Cardoso exemplified the best of the Olympic spirit, Brazil’s water polo team was in the running for the worst. After losing their first game to the United States on August 6, the Brazilians also lost to Germany on August 8. After the game, the Brazilian players charged the Hungarian referee, yelling that his officiating was unfair. Although some U.S. officials and athletes agreed with that assessment, the Brazilians were disqualified from further water polo competition.

One especially notable Brazilian athlete was swimmer Maria Lenk. The 17-year-old Brazilian champion was the only woman among the Brazilian athletes. She was also the first South American woman to compete in the Olympics.

Lenk competed in three events—the 100-meter freestyle, the 100-meter backstroke, and the 200-meter breaststroke. Unfortunately, she failed to reach the finals in her three events.

Nonetheless, Lenk was a pioneer for women’s sports in Brazil. When she returned to the Olympics in 1936, four other female swimmers went with her, along with one female fencer. Lenk remained a mainstay of Brazilian swimming, holding five Master World Records at the time of her death (while swimming) at the age of 92.

The 1932 Brazilian Olympic Athletes Return Home

When the 1932 Olympic Games concluded on Sunday, August 14, Brazil’s “coffee team” found itself in a tie with Uruguay for the fewest points with four. The Brazilians had won no medals. But leaving aside the disqualified water polo team, the athletes had represented their country well under very difficult circumstances. They had traveled to the Games on a shoestring budget, serving as coffee merchants as well as athletes. Some of the athletes never even got to leave the Itaquicê. Moreover, civil war had erupted in Brazil in the middle of their trip.

As Will Rogers put it in the Kansas City Star,

“Poor Brazil! They had come up here on a coffee boat, and after they had been out a couple of weeks their government changed hands, and the new government was trying to find out where the boat was. The athletes didn’t know what government or country they were really representing.”

The Brazilians planned to leave Los Angeles on August 16, but more financial troubles delayed the departure. The Itaquicê finally left for Rio de Janeiro on the morning of August 19. All of the coffee she had transported from Brazil had finally been sold. In return, the Brazilians had purchased some California produce for the return trip.

When the Itaquicê got back to Rio de Janeiro, the Olympic story wasn’t quite finished. The ongoing revolution made the homecoming difficult for some of the athletes. The 30 or so Olympians from the State of São Paulo had to take difficult, circuitous routes to their homes, traveling by freighter, train, truck, or even walking.

For all the athletes, it was a long way from the friendly competition and pageantry they had experienced under the Olympic torch. But they had shared an incomparable adventure as ambassadors for Brazil. In representing Brazil in Los Angeles, the members of the 1932 Brazilian Olympic team were ambassadors not only for athletics in Brazil but also for the coffee of Brazil.

Copyright © Brian Lokker 2021, 2023. An earlier version of this article was published on March 17, 2021, on my website CoffeeCrossroads.com.