Edwin Booth: The Greatest American Actor of the 19th Century

Edwin Booth (1833–1893) was one of the most highly acclaimed Shakespearian actors of all time and the most famous actor in 19th-century America. He achieved his fame through tragedy—his interpretations of Shakespeare’s tragic heroes.

But ironically, a real-life American tragedy threatened to undermine his achievements. When U.S. President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in 1865, the assassin was none other than Edwin’s younger brother and fellow actor John Wilkes Booth.

Destined for Fame

Born on November 13, 1833, at the Maryland country retreat of his father, Edwin Thomas Booth seems to have been destined for fame from the beginning. According to a story told by his sister Asia Booth Clarke on the night of his birth, there was a brilliant meteor shower, which the family interpreted as a sign that the boy would be blessed with luck and special gifts.

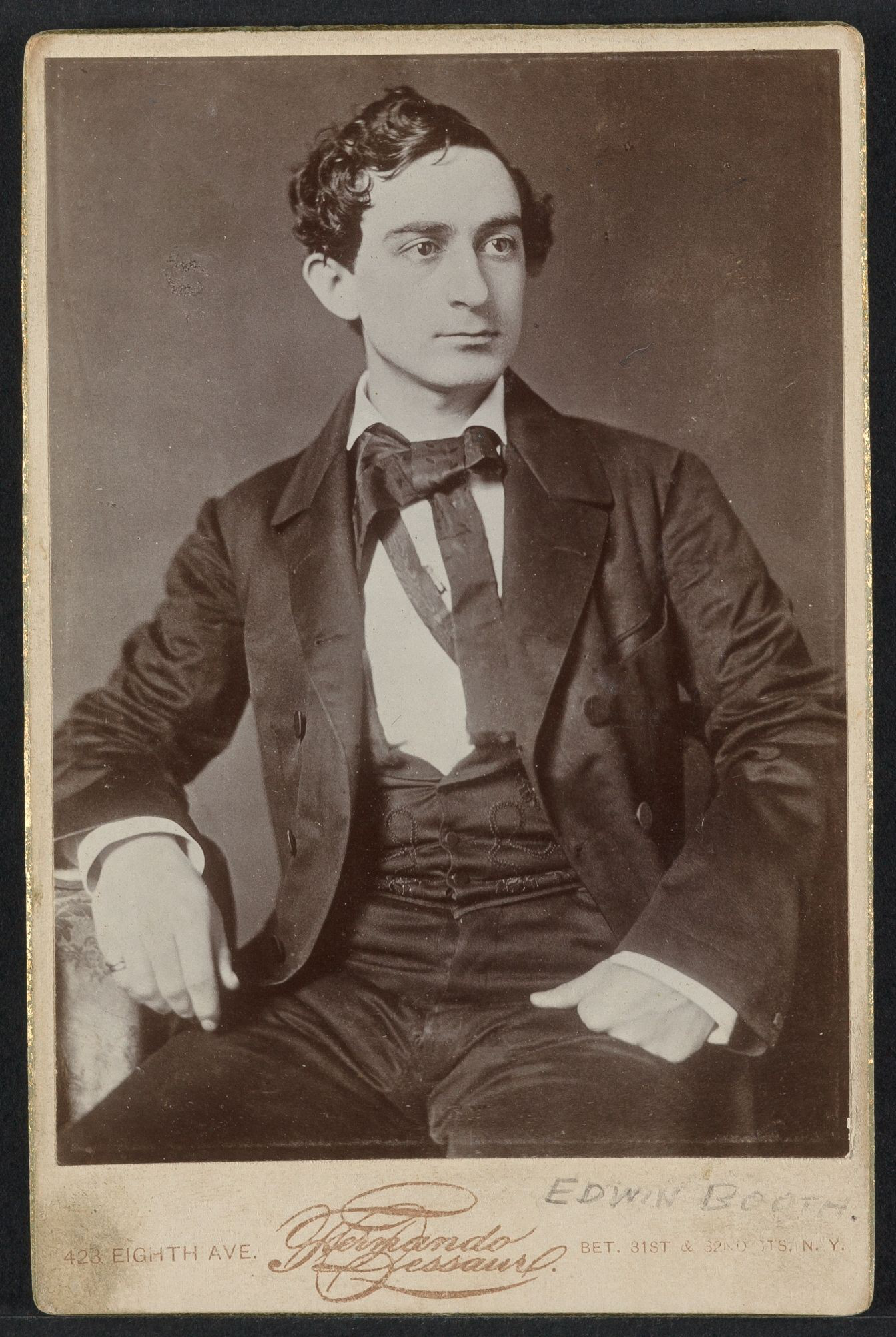

Edwin Booth photographed by Fernando Dessaur, 1856. (Houghton Library, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

It is not surprising that Edwin entered the acting profession or that he achieved success and fame in that profession. Acting was in his blood. His father was the prominent Anglo-American tragedian Junius Brutus Booth, and Edwin was named after two of Junius Brutus’s actor friends: Edwin Forrest, an American, and Thomas Flynn, an Irishman.

Yet the elder Booth did not press Edwin into becoming an actor. On the contrary, he urged that Edwin become a cabinetmaker or enter some other trade. But Edwin did follow in his father’s footsteps—as did two of his brothers, Junius Brutus, Jr., and John Wilkes—and Edwin eventually built a reputation for himself that surpassed his father’s.

Together they formed an acting “dynasty” that dominated the American stage for more than 70 years, from Junius Brutus’s first appearance in the United States in 1821 to Edwin’s death in 1893.

In Love with the Theater

Despite the elder Mr. Booth’s advice to his son to become a tradesman, he himself introduced Edwin to the acting profession. Edwin was his father’s traveling companion, and he fell in love with the theater and the applause of the audience.

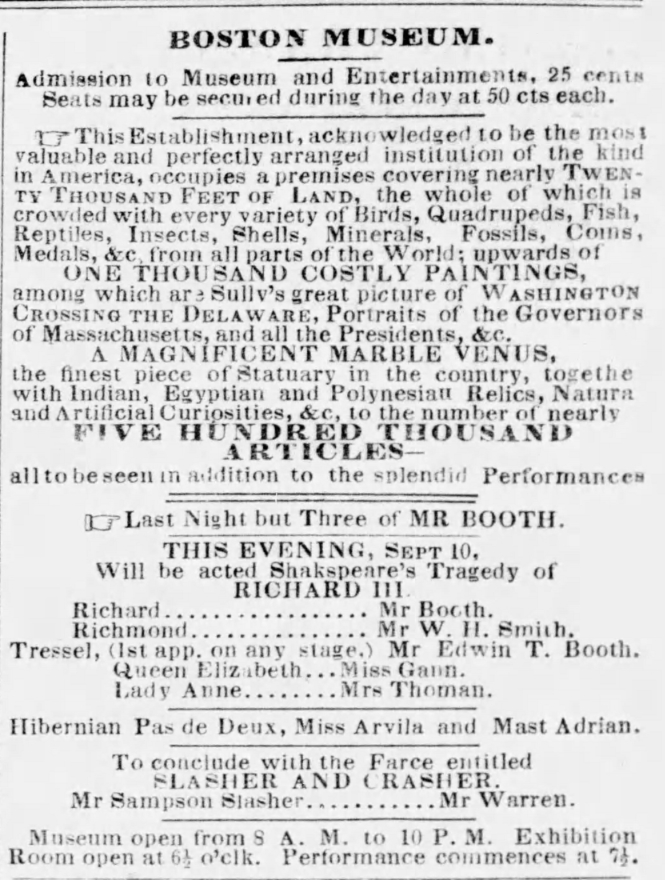

Edwin got his first taste of this applause when he was just 15 years old. On September 10, 1849, he appeared with his father in Colley Cibber’s version of Shakespeare’s Richard III at the Boston Museum. This debut came about somewhat abruptly: the actor cast in the minor role of Tressel did not want to go on and persuaded Edwin to play the part. Without consulting his father, Edwin agreed. Although the elder Mr. Booth did not approve, he did not stand in Edwin’s way.

Although Junius Brutus remained reluctant to have Edwin take up acting full-time, Edwin’s name began to appear more and more often in the playbill in his father’s productions. Within a year, Edwin was being billed regularly in supporting roles.

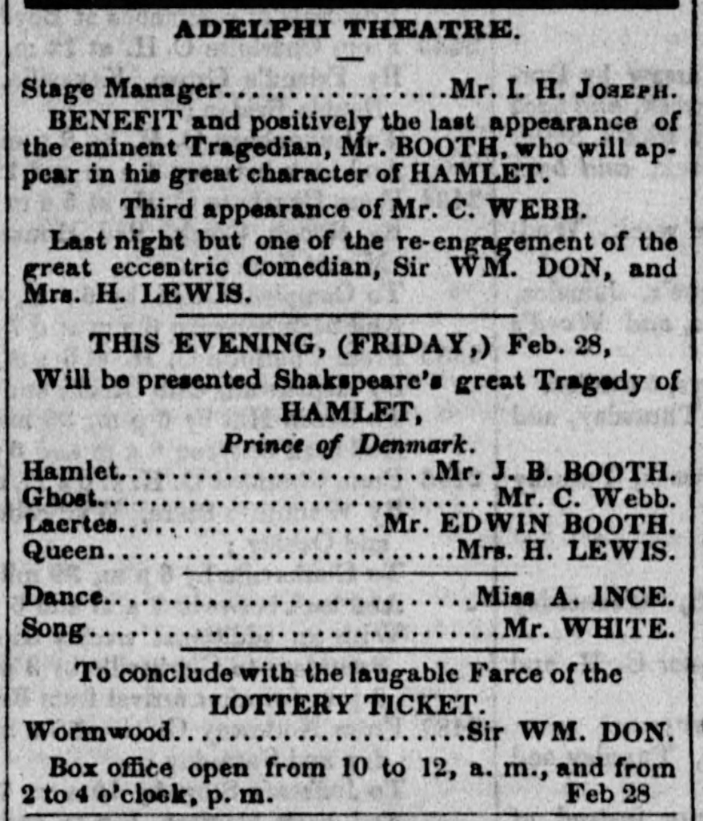

Some critics took notice of him, especially praising his work as Wilford in George Colman’s The Iron Chest and Hemeya in Richard Labor Sheil’s The Apostate. After a performance of the latter play at Washington, D.C.’s Adelphi Theater in early November 1850, the National Intelligencer praised his performance, saying it provided “ample evidence that the mantle of the father will fall upon the son.”

Boston Museum advertisement announcing Edwin Booth as Tressel in his first stage appearance, September 10, 1849. (Boston Evening Transcript, via Newspapers.com)

Emerging from His Father's Shadow

Edwin made an unscheduled debut in a leading role in 1851 at the National Theatre in New York. His father was to star as the Duke of Gloucester in Richard III, but just hours before the curtain was to go up, Junius Brutus claimed he was ill and announced that he would not take the stage that evening. He suggested that Edwin play the part instead. Edwin did so with little preparation and much apprehension, but his performance was favorably received.

An early theatrical announcement of Edwin Booth appearing in Hamlet with his father at the Adelphi Theatre, February 28, 1851. (The Daily Republic, Washington, D.C., via Newspapers.com)

Edwin was deeply attached to his father and loved touring with him, even though his father could be difficult. Even when they appeared together, Junius Brutus seldom offered overt encouragement for Edwin’s acting ambitions. But in San Francisco in 1852, during what would be their last tour together, when Junius Brutus was asked which of his three actor sons would carry on his great name in the theater, his answer was to put his arm around Edwin.

Junius Brutus died later the same year, and Edwin was on his own. By the spring of 1853, Edwin was playing the lead in Hamlet. On June 1, the Richmond Dispatch in Virginia noted that the San Francisco critics were calling Edwin’s performance as Hamlet “masterly” and predicting “a triumphant career on the stage.”

He continued acting in California for a while, then traveled with an acting company to Australia, and even to the Sandwich Islands, where he performed Hamlet for an appreciative audience. After returning to the United States, he appeared in numerous cities before opening in New York on May 4, 1857, in the leading role in Richard III. Although much of his reputation up to this point was a reflection of his father’s fame, Edwin now began to be appreciated for his own talent.

He continued to build his reputation in the following years, with many engagements in various leading roles in New York and other principal cities throughout the United States. He became very popular in Richmond, New Orleans, Memphis, and other Southern cities, but when the Civil War broke out he remained loyal to the Union and did not perform in the South for the duration of the War. Southern newspapers, however, continued to report on his activities and performances from afar.

In September 1861, Edwin began an engagement at the Haymarket Theatre in London. His first performance, as Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, earned him generally favorable but not enthusiastic reviews. The critics apparently couldn’t resist comparing the young American actor to the great English Shakespearean actor Edmund Kean, who had died almost 30 years earlier. The reviews for Edwin’s subsequent performances in other roles were mixed. On November 2, 1861, The Examiner acknowledged the great applause that Edwin received but sniped, “Mr. Booth is not in his right place as a Shakespearean tragic actor at a first-class London theatre.”

Most critics and audiences, however, disagreed with that negative assessment. After ending his run at the Haymarket, Booth had a very successful run at Liverpool’s Royal Amphitheatre. And his popularity in America was undiminished. After he returned from Europe in late summer 1862, audiences flocked to his performances, and the critics were enthusiastic. The Times-Picayune of New Orleans predicted that Booth would “startle New Yorkers out of their five senses by some remarkable new performances.”

Applause with His Brothers

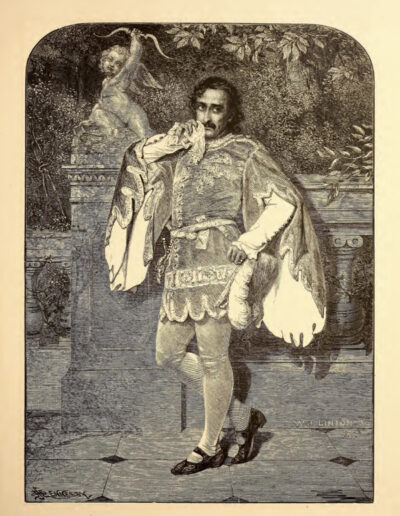

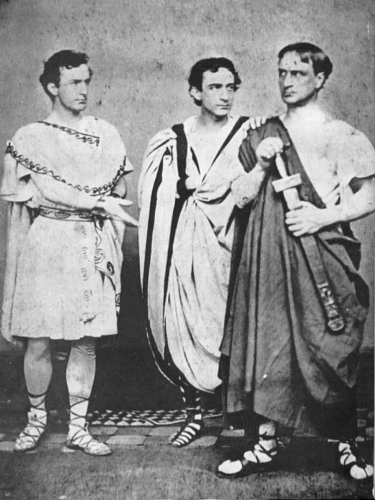

One of the most personally memorable nights of Booth’s career occurred on November 25, 1864. On this night Edwin and his brothers Junius Brutus, Jr., and John Wilkes, appeared together in a benefit performance of Julius Caesar at the Winter Garden Theatre in New York. Junius Brutus Booth, Jr., played Cassius, Edwin was Brutus, and John Wilkes took on the role of Marc Antony. The theater was standing-room only, and the brothers received tremendous applause from the audience.

The night almost ended in disaster. Confederate sympathizers had chosen that night to set multiple fires in the city’s principal hotels and public buildings. Soon after Act Two began, a fire broke out in the Lafarge House adjoining the theatre. But before the large audience could panic, Edwin stepped to the front of the stage and calmed their fears. The fire did not reach the theatre, and the play went on.

John Wilkes Booth, Edwin Booth, and Junius Booth, Jr. (L–R) in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in 1864. (The Life and Times of Joseph Haworth, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Best Hamlet of the American Stage

Edwin’s first appearance in the United States after his 1861–1862 European trip had been at New York’s Winter Garden Theatre on September 29, 1862, in the role of Hamlet. Commenting on that performance, the Boston Evening Transcript opined that “Booth is beyond all question the most intellectual, and accomplished actor now on the stage.”

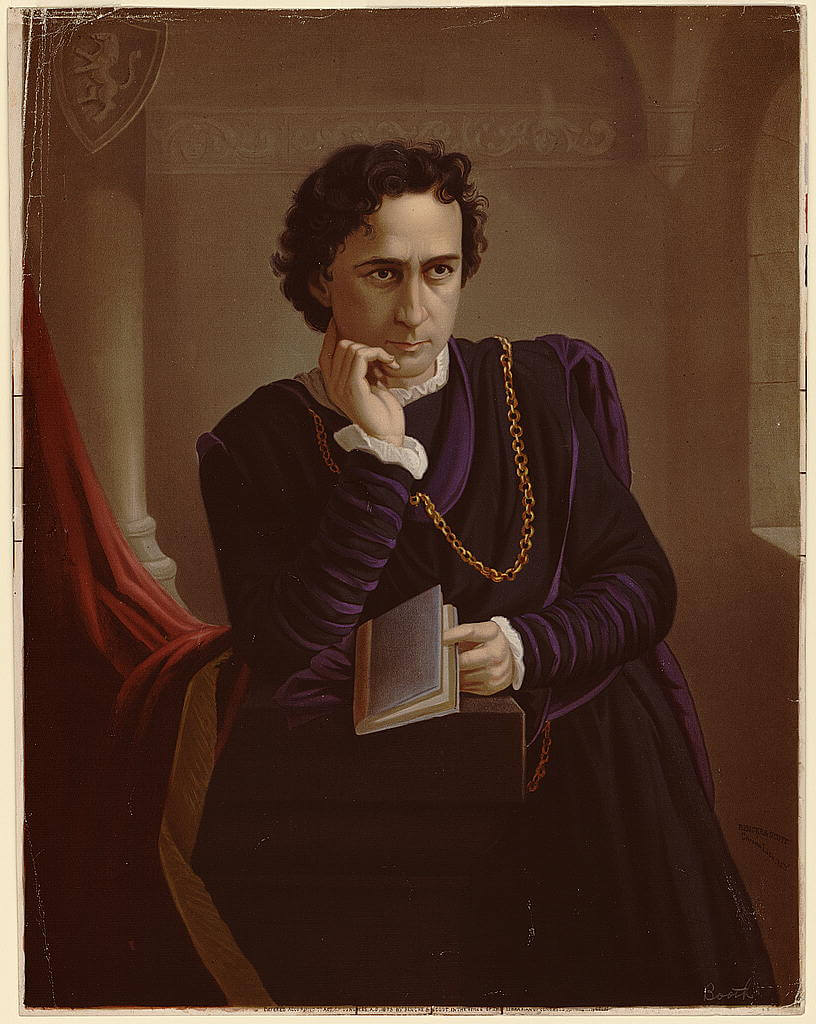

Edwin Booth as Hamlet, 1873. (Bencke & Scott, Library of Congress)

Although he played a variety of leading roles in Shakespearean tragedies and other plays throughout his career, Booth’s name became indelibly associated with the role of Hamlet.

His fame as the melancholy Dane was firmly established in the winter of 1864–1865. Beginning on November 26, 1864—the night after the Julius Caesar benefit with his brothers—he starred in a production of Hamlet that ran at the Winter Garden Theatre in New York for a record-setting 100 consecutive nights, concluding on March 22, 1865. His record lasted until 1922, when John Barrymore‘s 101 consecutive appearances as Hamlet surpassed it.

But for 19th-century critics and audiences, Edwin Booth had cemented his reputation as “the Hamlet par excellence of the American stage.”

Lincoln's Assassination and Its Aftermath

Tragically, less than a month later, on April 14, 1865, Edwin’s bond with his younger brother John Wilkes Booth was shattered when John Wilkes assassinated President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.

On the night of the assassination, Edwin was on a stage in Boston starring as Sir Edward Mortimer in a production of The Iron Chest by George Colman. He could not have suspected the irony of the words he spoke as the guilt-ridden Mortimer: “Where is my honor now? Mountains of shame are piled upon me!”

But the next morning, when he heard the news, Edwin felt exactly as Mortimer did in the play. He denounced his brother and withdrew from the theater in shame and humiliation, thinking his career was over because of his brother’s deed.

Less than a year later, though, he was back. Buoyed by the encouragement of many friends and admirers throughout the nation (and with his family in debt), Edwin braved death threats to return to the Winter Garden Theatre as Hamlet on January 3, 1866. He received a rousing welcome that night, as well as in subsequent performances in New York and other cities. His career again began to flourish and would continue to do so for 25 years.

Booth also took some comfort from the coincidental fact that he had once saved President Lincoln’s son Robert from serious injury or death. On a crowded train platform in Jersey City, New Jersey, Robert was caught in the gap between the platform and a moving train. Edwin, who happened to be in the same crowd, recognized the danger and pulled Robert to safety.

Edwin Booth, Theatrical Entrepreneur

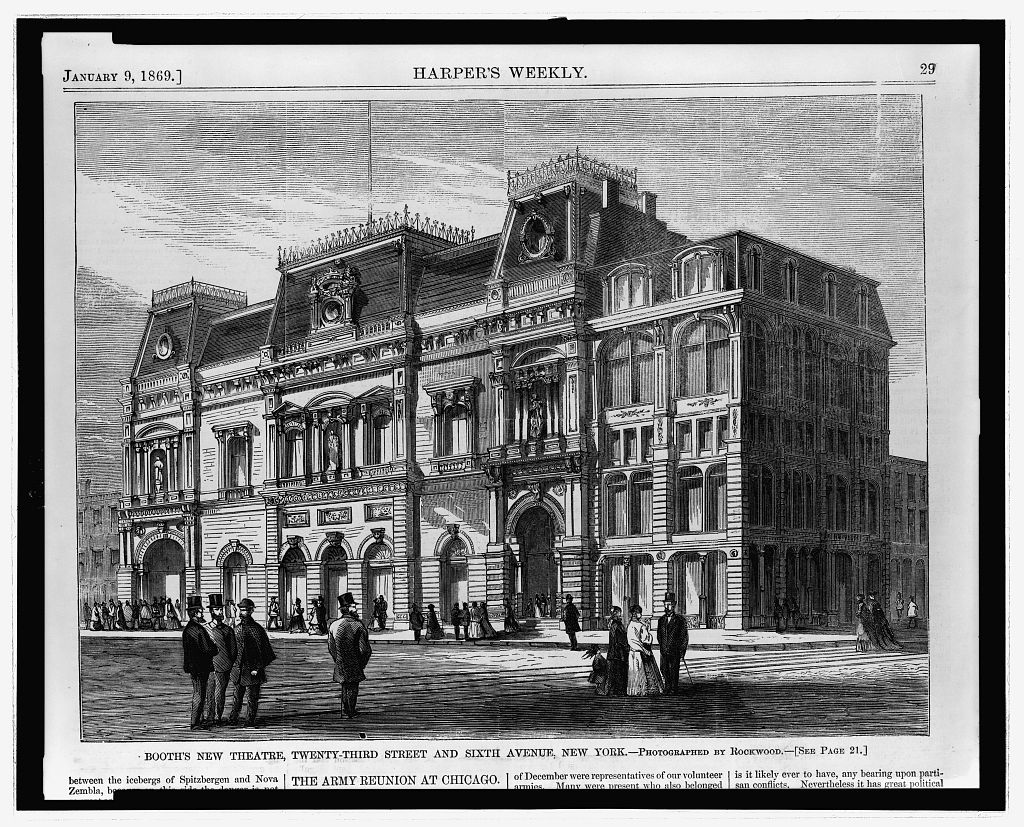

On February 3, 1869, Edwin opened his own Booth’s Theatre in New York with a production of Romeo and Juliet, in which he starred as Romeo. The magnificent building cost over a million dollars and was the culmination of Booth’s ambition to build a modern, artistically and aesthetically superior theater that would do justice to his art.

Booth's Theatre, 1869. Print in Harper's Weekly after a photograph by George Gardner Rockwood. (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Booth staged and performed in many Shakespearian plays in Booth’s Theatre. His productions were based on Shakespeare’s original texts, an innovation for the time. Unfortunately, although the theater was an artistic success, it was a financial failure for Booth. He was forced to resign from the management of the theater after several years.

Personal Tragedies

Despite his success on the stage, Edwin was beset by other personal tragedies in addition to his brother’s assassination of President Lincoln. His first wife, actress Mary Devlin, died in 1863 after only three years of marriage, leaving him with a young daughter, Edwina. In 1869 Edwin married again, to Mary McVicker, also an actress, who had appeared with him as Juliet in the Booth Theatre’s opening night production of Romeo and Juliet. In 1870 she gave birth to a son who lived only a few hours. Mary then began to suffer from fits of rage, bordering on insanity. While accompanying Edwin on his trip to London in 1881, Mary’s condition worsened, and she died on November 13, Edwin’s birthday.

Meanwhile, in April 1879, Edwin survived an assassination attempt that was reminiscent of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination by John Wilkes Booth. While Edwin was delivering a soliloquy in the last Act of Richard II at McVicker’s Theatre in Chicago, a young man named Mark Gray Lyon shot at him twice. Fortunately, both shots missed. The would-be assassin was judged to be insane and remanded to an asylum.

To many observers, Edwin Booth was the true tragedian: a tragic figure in his own right. To the outside world, he often seemed melancholy. But he possessed a spiritual faith that allowed him to bear the personal tragedies of his life with patience and self-control. And those who knew him well testified to his joie de vivre, which was masked by shyness.

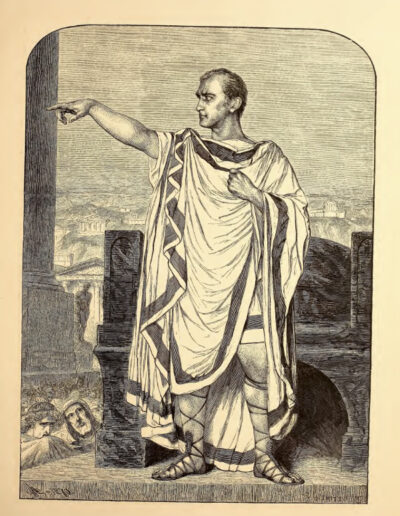

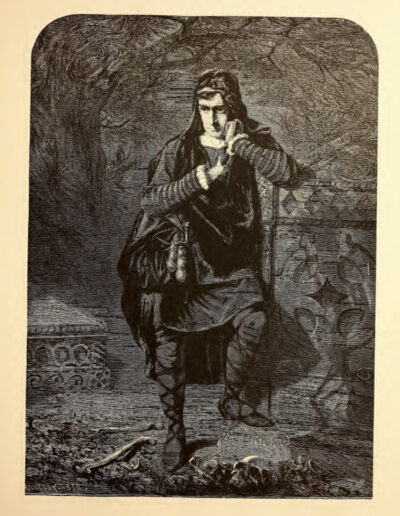

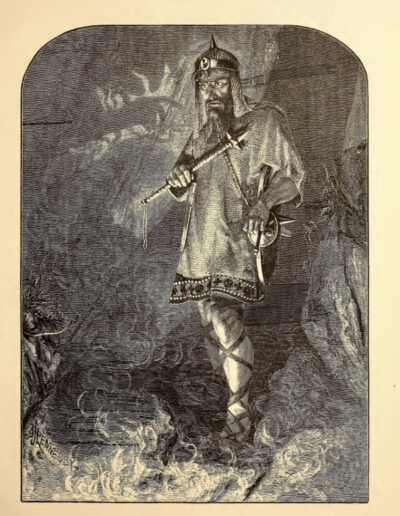

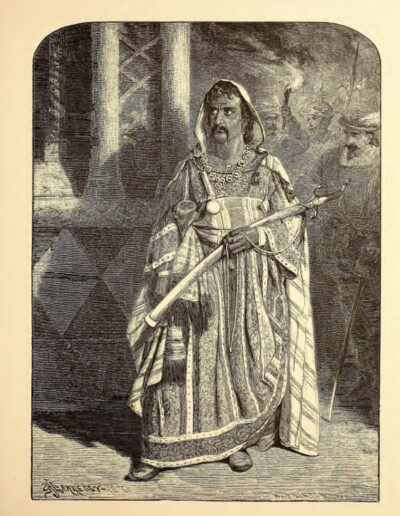

Becoming the Character

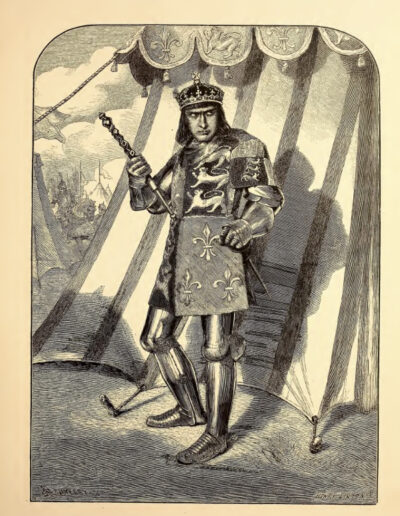

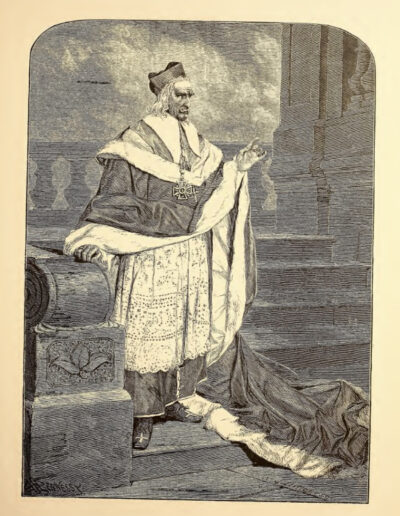

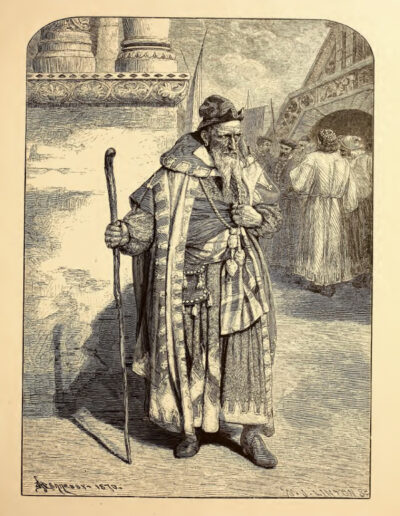

Edwin Booth enjoyed success on the stage until a small stroke precipitated his retirement in 1891. He was widely recognized as the leading American tragedian of his time, but he also appeared in comic roles. This portrait gallery shows him in some of his most famous roles.

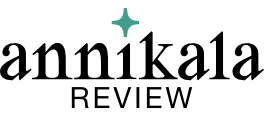

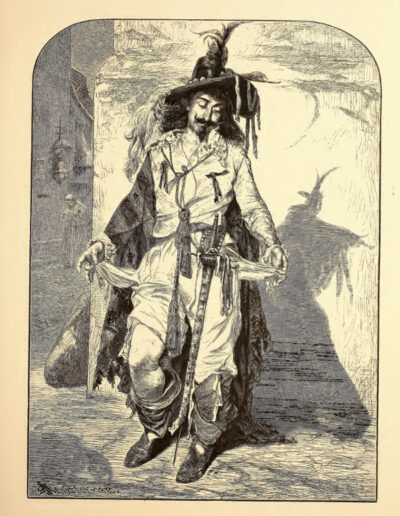

Don Caesar de Bazan

Edwin Booth as Don Caesar de Bazan in Dumanoir and d’Ennery’s “Don Caesar de Bazan”

The portraits were drawn by W. J. Hennessy and engraved by W. J. Linton. They appear in the book Edwin Booth in Twelve Dramatic Characters (1872), which also includes a biographical sketch of Booth by William Winter, a prominent drama critic who was Edwin Booth’s friend. The book also lists a portrait of Booth as King Lear among the illustrations, but that portrait appears to be missing from the available copies of the book.

Edwin’s renown was broadened by new engagements in London in 1880–1881 and on the Continent in 1883. In London, he appeared with Henry Irving, the reigning English tragedian, and the two developed a relationship of mutual admiration. In Germany, he was praised extensively as the best Hamlet ever seen on the stage.

Some critics who had admired Junius Brutus Booth said that Edwin’s great reputation as an actor was largely inherited from his father and due only in small measure to his own talents. Edwin himself acknowledged his debt to his father. But Edwin Booth was an actor of a new generation, and the distinction between father and son was not a difference in ability but a difference in style.

His father’s style, like that of other actors of his generation such as Edmund Kean and Edwin Forrest, was bold and bombastic. Edwin took a new, more modern path: he approached his roles with more thoughtfulness and sensibility, striving to become the characters he played, to creep into their skin. Not all critics appreciated Edwin’s approach. His performances were sometimes criticized for being too intellectual and not emotional enough.

The Perfect Hamlet

Even among critics who praised Edwin’s performances, there was disagreement as to which of his roles was his best. But among the public, there was no doubt—Edwin Booth’s best role was Hamlet. Theatergoers associated Edwin’s outwardly melancholic nature with the same characteristic of Shakespeare’s Danish prince. Even Edwin’s physical appearance fit the popular conception of Hamlet:

“His light and graceful figure, his pale face bordered with dark and clinging hair, his features well chiseled and mobile with expression, his large and handsome eyes—all these personal attractions are commonly known and recognized as fitting him peculiarly for the character of Hamlet.”

To the public, Edwin Booth seemed to be Hamlet.

Edwin Booth, Innovator and Celebrity

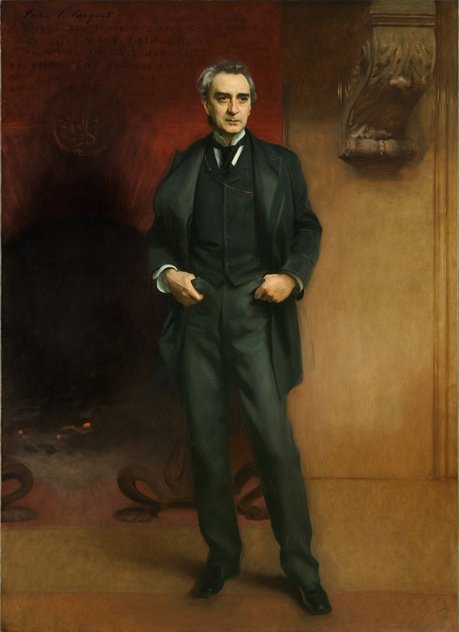

Portrait of Edwin Booth, 1890. (John Singer Sargent, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Edwin Booth was an innovator in American theater. As a theatrical entrepreneur, he built Booth’s Theatre, a modern artistic and aesthetic achievement. In 1888, he also founded The Players, a social club in New York City for actors and other professionals. His productions were characterized by sumptuous sets, realistic “stage business,” and the return to original texts. As an actor, he introduced a more modern, natural style of acting to the stage.

What’s more, Edwin Booth was a very popular American figure, a celebrity, in the second half of the 19th century. He captured America’s imagination by bringing the glory of Shakespeare to the stage during the otherwise grim period of the Civil War and Reconstruction—despite his own intimate connection with the single most shocking and tragic event of that tragic time for America. Ironically, through his mastery of the art of dramatic tragedy, he surmounted his own private tragedies and helped to heal America’s public tragedy.

Copyright © Brian Lokker 2011, 2023. An earlier version of this article was published on HubPages.com in 2011 and was subsequently featured on Owlcation.com.